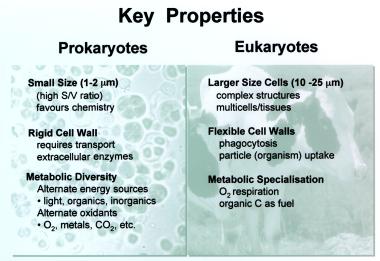

The Toughness of LifeAnother notable feature of life on Earth is that of its toughness and tenacity. In order to consider this issue, we should briefly return to the discussion of prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Some of the key properties used to distinguish the prokaryotes from their more complex eukaryotic cohorts are shown in Table 1. The eukaryotes are defined by the presence of a nucleus and nuclear membrane (eu = true; karyon = nucleus), and in general are characterized by complex structures, complex behavioral features, and simple metabolism. Their metabolism is primarily via oxygen-based respiration of organic carbon, and the sizeable energy yields from these processes are used to support their complex structural and behavioral investments. Basically, plants make organic carbon via photosynthesis, and animals eat the plants (and other animals), leading to the kind of complex communities we easily recognize under the general heading of trophic levels or predator-prey cycles. The very existence of complex structures (both intracellular organelles, and multicellular tissues and organs) renders the eukaryotes sensitive to environmental extremes often easily tolerated by their structurally simple prokaryotic relatives (e.g., above 50 C, it is unusual to find functional eukaryotes).

Figure 5. Properties of the prokaryotes and eukaryotes. The small anucleate organisms known as prokaryotes share some properties that allow us to group them into functional domains that are quite different from their eukaryotic counterparts. On the other hand, the prokaryotes are the environmental “tough guys,” tolerant to many environmental extremes of pH, temperature, salinity, radiation, and dryness. I refer to these organisms as the sundials of the living world - tough, simple, effective, and nearly indestructible. Some of the fundamental properties that distinguish them from the eukaryotes are shown in Figure 5. First, they are small -- they have optimized their surface to volume ratio so as to maximize chemistry. On the average, for the same amount of biomass, a prokaryote may have 10-100 times more surface area. Thus, for a human whose body mass may include a few percent (by mass) bacteria (as gut symbionts), the bacteria comprise somewhere between 24 and 76% of the effective surface area! In environments like lakes and oceans, where bacterial biomass is thought to be approximately 50% of the total, the bacteria comprise 91 to 99% of the active surface area, and in anoxic environments, where the biomass is primarily prokaryotic, the active surface areas are virtually entirely prokaryotic. In essence, if you want to know about environmental chemistry, you must look to the prokaryotes!

Contributed by: Dr. Kenneth Nealson |