Analysis of Responses to Questions 3-5The first two questions of each questionnaire served to identify the respondent. Questions three through ten provide the content. Questions 3, 4, and 5 are of particular interest, because they deal most directly with variants on the focal question.

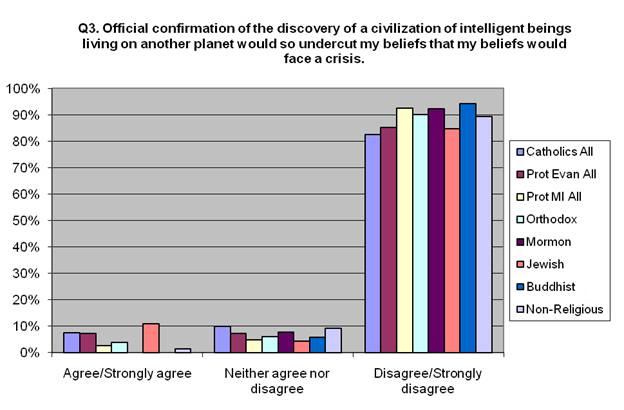

Question 3 asks the respondent to attend to his or her own personal religious beliefs. Significant here is that among those who self-identify as Roman Catholic, mainline Protestant, evangelical Protestant, Orthodox Christian, Mormon, Jew, and Buddhist, the vast majority expect no crisis to develop when learning of ETIL. No evidence of widespread anxiety or fear that their religious belief system might be threatened surfaces here. “Hey,” comments a mainline Protestant respondent, “I’d share a pew with extraterrestrials any day.” If adherents to the world’s religious traditions foresee no threat, then the widespread assumption about an impending crisis fails to gain confirmation here. The comments accompanying the survey responses indicate that this is the majority view among Christians and non-Christians alike. “Finding ETI, I believe, would be a profound and wonderful event,” commented a mainline Protestant. “From an evangelical Christian perspective,” wrote another respondent, “the Word of God was written for us on Earth to reveal the creator....Why should we repudiate the idea that God may have created other civilizations to bring him glory in the same way?” One Orthodox Christian commented: “Nothing would make me lose my faith. God can reach them if they exist.” An evangelical surmised that “there is nothing in Christianity that excludes other intelligent life”, while another argued that “the Bible allows for the possibility of advanced beings who can take on human form - 2 Peter 2:4 and Jude 6.” The place of Jesus Christ and his work of salvation is important to Christians. A Roman Catholic remarks: “I believe that Christ became incarnate (human) in order to redeem humanity and atone for the original sin of Adam and Eve. Could there be a world of extraterrestrials? Maybe. It doesn’t change what Christ did.” Similarly, an evangelical Protestant contends that Christ’s “death and resurrection were universally salvific,” valid for ETI, while another evangelical says, “I believe that the eschatological claim that ‘every knee will bow’ to Jesus as God applies to extraterrestrial intelligent beings (even if they don’t have knees).” Among the few Muslim respondents, one wrote, “Islamically, we do believe that God created other planets similar to Earth”; and another seemed to concur, “only arrogance and pride would make one think that Allah made this vast universe only for us to observe.” One Buddhist speculated that “ETs would be, essentially, no different from other sentient beings, i.e., they would have Buddha Nature and would be subject to karmic consequences of their actions.” A self-identified mystic trumpets: “my belief in God is absolutely unaffected by extraterrestrial life.” Finally, “discovery of ET would not affect my personal belief system because I am a stone atheist.” Some of the religious respondents hinted they believe in contact optimism - that is, they expect that extraterrestrial intelligent life forms exist and they positively look forward making contact. Others placed themselves with the rare earth camp - that is, they believe that life on earth is so rare that a second genesis of life is not likely to have occurred anywhere else in space. The rare earth position does not necessarily make the beliefs of the person who holds it fragile or vulnerable. One evangelical Protestant cheerfully remarked: “I don’t think they are out there. But if they are, that’s cool.” Despite the clear majority who feel comfortable with knowledge of ETI life forms, a minority of individuals perceive a challenge to their religious faith posed by gaining knowledge of ETI. The speculative assertion that “the foundations of my religion (Catholic) and many others may be shaken by such a discovery” appeared among the comments. One evangelical Protestant states, “I personally believe that Satan, the enemy of Jesus, will attempt to deceive the world into believing he is an ET, and many will fall for it....There are no ETs in the sense of physically evolved alien creatures. There are ETs in the sense of spiritual beings (angels and demons).” A stereotype sometimes surfaces: fundamentalist believers are the most vulnerable to a religious crisis because ETI does not fit the fundamentalist worldview. “Confirmation of alien intelligence might cause a crisis for Protestant fundamentalism and Islam, for which their scriptures’ failure to predict the aliens could be quite damaging,” writes a non-religious respondent. The Peters survey did not try to ferret out fundamentalism as a separate category. Respondents who belong to the fundamentalist tradition generally locate themselves within the more inclusive evangelical Protestant category. The category of “Protestant: evangelical” includes conservative Christians, some of whom but not all of whom are fundamentalists. The survey data alone do not discriminate. However, some respondents volunteered comments, suggesting that they fit the description of fundamentalists. Of these, a few did voice apprehension about the prospect of ETI communication. “Nothing I can find in scripture altogether rules out extraterrestrial life, but on balance I think it is very unlikely that such a thing exists.” Within the scope of Christian theology, it appears that little if any beliefs preclude the existence of extraterrestrial beings. Their presence would at most widen the scope of one’s understanding of creation and create some puzzles for how Christians understand the work of salvation (Peters, chapter 3). Jews and Buddhists, it appears, would experience even less friction in their belief systems should confirmation of the existence of ETI be established.

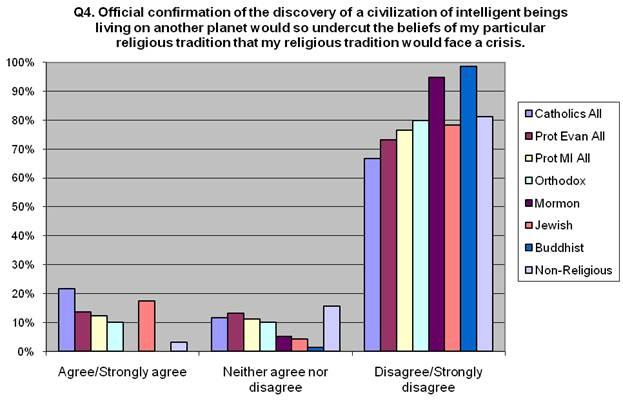

Question 4 shifts from personal beliefs to the beliefs of the religious tradition to which the respondent self-identifies. Can we distinguish slightly between one’s individual belief and the belief he or she shares with tradition? “There is nothing in Christianity that excludes other intelligent life,” commented one evangelical Protestant. Another added: “I honestly don’t think ETI existing has any affect on the Bible and the Christian faith”; whereas still another hinted at doubt: “my personal religious tradition would have trouble if there were ETs who were sinful.” Another evangelical pressed us to prepare for the eventuality: “the religious tradition with which I identify (Protestant Evangelical) is not prepared for the day we do make contact; but we need to start thinking this out and become prepared.” Responses to Question 4 tell us that very little fear is registered regarding a possible threat to one’s inherited belief system. However, the numbers are not identical to those of Question 3. They drop slightly in the Disagree/Strongly disagree option. Might this indicate a slightly higher level of confidence with one’s own individual beliefs than with the beliefs of the larger religious tradition to which one belongs? Here is what one Buddhist told us: “As a Mahayana Buddhist, with a worldview that includes in scriptures Buddhas and bodhisattvas from many different world systems, such information [news about ETI] would not be shattering theologically, though of course institutions and practices might reverberate.” One respondent offered this: “the strict followers of religion would be the most affected by such a finding of extraterrestrial life whereas the loose followers such as myself would welcome the new discovery.” Might a small number of respondents worry slightly more about others in their tradition than they do about themselves? This interpretation could be supported by data drawn from another survey. A 2007 survey of more than 35,000 Americans conducted by the Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life uncovered a trend that may be indirectly relevant. Whereas conventional wisdom might suggest that the more religiously zealous a person is the more intolerant he or she would be, this survey indicates that the opposite is true. Zealous Americans are tolerant, even welcoming religious perspectives that differ from their own. To the statement, “many religions can lead to eternal life,” for example, 57 percent of evangelical Protestants agreed as did 79 percent of Roman Catholics. So did the majority of Jews, Hindus, and Buddhists. What this suggests is “a broad trend toward tolerance and an ability among many Americans to hold beliefs that might contradict the doctrines of their professed faiths” (Banerjee).Now, this survey is limited to Americans and it does not test directly for openness toward ETI. However, if it is in fact the case that many religious people are capable of holding “beliefs that might contradict the doctrines of their professed faiths,” then it might follow that those who welcome ETI into their worldview could do so even if they worry slightly about doctrinal fragility in their own respective religious tradition. Note how high Mormons score. Many Mormon respondents added comments to the effect that belief in ETI is already a part of Mormon doctrine. “My religion (LDS, Mormon) already believes in extra-terrestrials.”

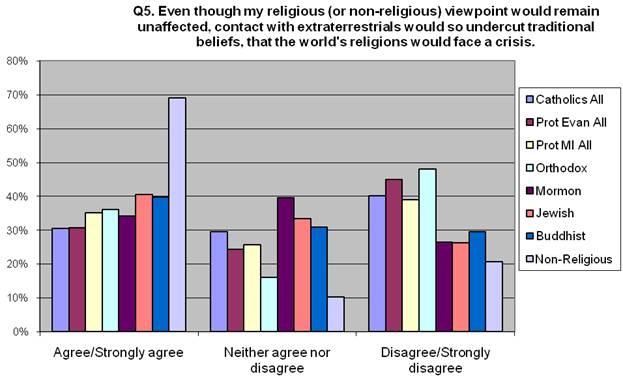

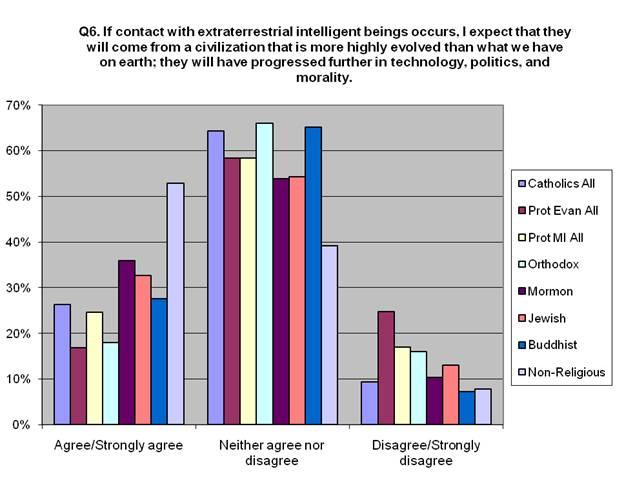

After seeing how firm the Disagree/Strongly disagree position is taken by adherents to the major religious traditions in Questions 3 and 4, the contrast with Question 5 becomes illuminating. A slight majority remain in the Disagree/Strongly disagree category. Yet, the Agree/Strongly agree cluster is significantly higher than in Question 3 and still higher than in 4. Those who identify with a major religious tradition give a modest degree of credence to the forecast that the world’s religions - religions other than their own perhaps - might confront a crisis. Some degree of credence only, we stress; yet, it is still worth noting. Could it be the case that an individual religious believer is slightly more worried about someone else’s beliefs than his or her own? At minimum, respondents were willing to say that some religious traditions are more vulnerable to a crisis than others. A Buddhist projected a crisis for some religions but not others: “lumping together all the world’s religions is a conceptual error (as in Question 5). The religions of the book (the Abrahamic traditions) would have a very different set of reactions than the Asian traditions.” A Buddhist typically belongs to an Asian tradition; so in this case we seem to see an Asian who is worried about the three Abrahamic (monotheistic?) traditions. A Jehovah’s Witness tried to gain precision: “I think #5 should say ‘some world religions’ would be affected,” not all. Some respondents saw the crisis precipitated by news of ETI as temporary, leading eventually to a strengthening. “I believe in the short-term there will be crises...but in the mid- and long-range, pre-contact belief will return to normal or perhaps slightly strengthened,” wrote a mainline Protestant. Now, let us turn to the 205 respondents self-identifying as non-religious. What happens in Question 5 may be quite revealing. We will look again at Question 5, comparing the non-religious with all the religious traditions grouped together.

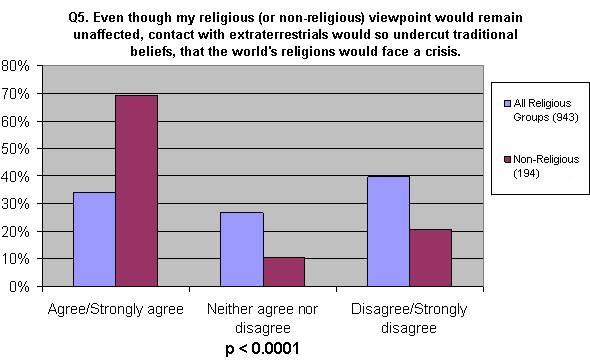

In this chart comparing all those who identify with one or another religious tradition to non-religious respondents, we computed the P value. The P value is much less than 0.0001. This gives us confidence that this comparison is not the result of a mere sampling error. P represents the probability that the two groups are indeed the same, presuming that any apparent difference in a given sample is just the result of random chance. Chance plays a part whenever a sub-sample of a population is taken. Might the difference between religious and non-religious be due merely to a sampling error? We do not think so. The difference between these two groups in our sample would only come about by chance in less than 1 out of 10,000 samples taken from groups were indeed the same. With this confidence, we observe how a significant majority (69%) of those who identify as non-religious project a crisis for religion. This is twice the average of those who are affiliated with a religious group (34%). That is, the non-religious have a much more negative forecast for religion than do adherents to religion. What might this suggest? Could it suggest that non-religious persons think of themselves as more open to ETI than their religious neighbors? Might this observation speak directly to what some astrobiologists assume, namely, that as scientists they are more open minded than their closed minded religious neighbors? One self-identified non-religious respondent warned strongly, “our religions, most of which are dogmatic, would be rocked.” Another wrote with nuance: “encounters with aliens will so frighten the ordinary human that he/she will cling more strongly to their beliefs.” From the point of view of the non-religious, religious beliefs are fragile and vulnerable to a crisis. As we summarize our findings from Questions 3, 4, and 5 of the Peters ETI Religious Crisis Survey, it appears that people who embrace a traditional religious belief system do not fear for their own personal belief; nor are they particularly worried bout their own respective religious tradition. A shred of evidence suggests that believers in one religious tradition might be more

inclined to impute fragility to other religions to which they do not subscribe or about which they know little. Non-religious people seem to know too little about religious people, because they are mistaken in their assessment of the fragility of religious beliefs. Our central finding is this: the hypothesis that the major religious traditions of our world will confront a crisis let alone a collapse is not confirmed by the Peters ETI Religious Crisis Survey. Furthermore, it appears that non-religious persons are much more likely to deem religion fragile and crisis prone that those who hold religious beliefs.

Printer-friendly | Contributed by: Ted Peters |