|

|

Now, I understand that when you give a public lecture you're supposed to start with a joke to get people's attention. But I'm a philosopher and philosophers are not noted for having a good sense of humor. So I don't have a joke for you. But I'm also a professor and I know a foolproof way to get attention, that is to announce a pop quiz. Now, don't worry, you don't have to turn this in. You're not going to get a grade; you didn't pay enough to get a grade for this (laugh). See I told you we don't have a sense of humor.

Here's the question. Which of the following comes closest to your view of human nature?

|

Pop Quiz Which of the following comes closest to your view of human nature? 1. Humans are made of three parts; e.g., body, soul and spirit. (trichotomism) 2. Humans are composed of two parts: (dualism)

3. Humans are composed of one ‘part’: a physical body (materialism/physicalism) 4. The question doesn’t make sense! |

1) Humans are made of three parts, for example, a body, a soul and a spirit. This is a view that's called trichotomism.

Option number two: Humans are composed of two parts--this is called dualism, and there are two versions available in our culture: A body and a soul, or a body and a mind.

Third option: Humans are composed of only one part, a physical body. And this position can be called either materialism or physicalism. And if you don't find yourself there you can always opt for number four. That question doesn't even make any sense. I put that in there because I actually think that that's probably what many of the biblical authors would say if they were forced to answer this quiz.

So I'm going to ask you for a show of hands. How many of you would choose option number one? That's a pretty good number.

Option number two, dualism of either sort. Okay.

Option number three, physicalism. A few--two or three.

How about number four? How many of you would choose number four? All right. Good.

Well, that's kind of the sort of spread that I always get when I lecture on this subject. It's interesting that this is a topic that is rather important. I mean, we're talking about the very nature of ourselves as human beings. And there's a vast amount of disagreement on this issue. But interestingly, it's a topic that has not been talked about in public. And that's the reason that we can have a group of people and nobody can really guess who is going to say what when they're asked to answer that question.

However, as Adrian pointed out in his introduction, it's a topic that's getting to be more and more a topic of discussion and debate in our culture. And to a large extent, this has to do with the developments in the neurosciences. I think you quoted--it was Francis Crick that you quoted--arguing that for Christians the notion of you might see a detachable mind or soul as an essential part of their teaching. So if the neurosciences can show that there is no such thing, then poof, argument against Christianity in one fell swoop.

So it's important for Christians to talk about this issue and discover for ourselves whether dualism or trichotomism really is essential. My own view is that it's not. But it's not my job to argue that here today; I'm here as a philosopher not a biblical scholar or a theologian--thank heavens.

So what I'm going to do is take option number three, physicalism, as the best alternative; I'm going to assume that it fits better with science than the other options do. And I'm also going to assume for present purposes that it's at least as compatible with biblical and theological teaching as dualism or trichotomism is.

My job then is to deal with the issue of reductionism. So option number three (Physicalism) actually hides two very different views here: A reductive view of physicalism or materialism and a non-reductive view of materialism or physicalism.

First of all, I want to try to make that distinction clear to you. And in both this talk and the one after lunch, I'm hoping to make it clear that it's possible to be a physicalist but not make the reductionistic moves that would, in fact, be disastrous for Christians and other religious believers. And, in fact, it would be equally disastrous for anybody who cares about the rationality of human thinking processes.

I'm going to start from the assumption that science makes dualism and trichotomism very implausible and that Jews and Christians never needed those views in the first place. And I will set out to try to develop a non-reductive view of physicalism.

Now, to do that, I'm going to start by thinking about the sciences. And, in particular, I want you to think about how the various physical sciences fit together. You may have mused about this when you were a college student or those of you who are college students may think about it sometimes.

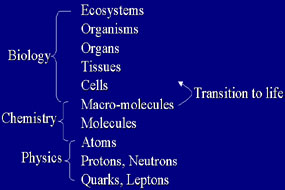

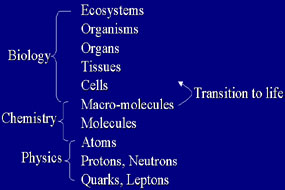

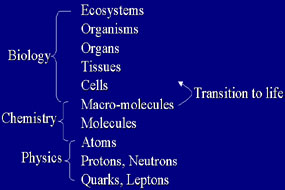

One way to think about it is this: We can make a hierarchy of the sciences. You go to physics class and you study the smallest particles making up the physical universe. You go from there to chemistry class and there you study how those smallest particles combine to make atoms and how atoms combine to make molecules. You go then to biology class and there you study how biological processes depend on the behavior of very large complex molecules just as we saw in Cynthia Fitch's lecture before the break. So we can think of the relations among the sciences and what they study something like this:

|

Physics studies the smallest particles of matter, as we know them--I hope I've got them listed more or less right for present purposes. Chemistry studies those same particles in larger configurations. And notice that there is an overlap between the domain of chemistry and physics. Biology studies a variety of levels, beginning with the macromolecules that you saw in the lecture on genetics earlier.

Now, notice that I've indicated in the hierarchy transition to life. And that's approximate. From that there are a lot of levels missing between the macromolecules at a cell, which is a very, very complex entity as compared with the molecules that make it up.

Now, there was a huge controversy in biology and philosophy of biology as recently as the 1930s. The question was: Do you have to add some non-material entity to non-living matter in order to get a living being. For example, do you have to add some sort of vital force or to use an older term from Aristotelian biology, do you have to add an Entelechy. Or, to put it in terms of our debate about physicalism versus dualism, do you have to add a soul. Because one of the functions that was originally attributed to the soul in medieval thought was that it was the life force, it's what makes things alive.

So the controversy raged. It was called the vitalist controversy but it's been pretty well settled by now. And I don't know if you could find a biologist these days who thinks that you do have to add some additional substance to non-living matter in order to get a living being. Rather, what's needed in order to get life is new structure. You restructure the materials that were already available into a more complex organization.

Now, an aside here, I'm not arguing against divine creation when I'm talking about getting life out of matter. You can put it in purely scientific terms or you could put it this way: God did not have to add any non-material stuff to create life. He only had to organize the matter that was there.

Life is the result of increased complexity, new forms or structures. But, of course, it's not all equally complex things that are alive. Life depends not just on new structure, but it depends on a new structure that allows for new kinds of functions.

Now, as I mentioned, even the simplest of actual cells is incredibly complicated and it's too complicated to portray here. So the question is: What would you need to have the very, very simplest example of something living?

Well here's what the philosophers of biology would say: They say that you can define something as alive if you can meet these three conditions. First of all, it's self contained, it has some sort of a boundary. And so here's my drawing of the simplest possible cell and it simply has a boundary that separates it--what's inside from what's outside.

|

|

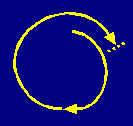

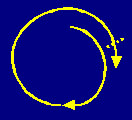

Second, it has self maintenance. That is, whenever it looses energy or matter to the environment it has a way of taking in energy or matter to replace it in order to replenish itself.

Down underneath here, non-life, there's not enough coming in for it to continue in a circle.

|

If you get enough material coming in that it can perpetuate itself then you've got one of the criteria for life available. So self-containment and self-maintenance, the possibility of repairing itself.

|

|

And then finally, to have life you need reproduction. And so it has to expand or grow.

|

And if you can imagine it growing enough that the second piece can be detached somehow and take off performing these functions on its own, then you've got a primitive form of reproduction.

|

And so if you've got those three conditions met, by definition you can say that your little blob of organic matter is alive.

So we reject vitalism. All you need for life is matter, properly organized, so it can perform these functions.

At this point, I want to hone in on this question of reductionism versus non-reductionism.

Here's one way of sort of intuitively making the distinction. The reductionist says--hah--the settling of the vitalist controversy shows that all that really exists is the stuff that physics studies. The non-reductionist replies, well, in a sense that's true; that is, if you took away all the stuff the physicists study then all living organisms would be gone also and there would be nothing left. But it's not true to say that there are only quarks and leptons. In addition, there are things like sulfur atoms and salt molecules and DNA and bacteria and trees and frogs. All of these things are just as real as the quarks and leptons and protons and neutrons.

|

Now is this just a verbal dispute talking about what's really real as opposed to what just is sort of real, appears to be real?

Well, let me give you an even simpler analogy. Imagine a couple of kids playing with Legos. Now, I assume that everybody knows what Legos are. I teach at a very culturally mixed environment and so I have to explain in my classes that these are the little plastic blocks that snap together and kids build things out of them.

Now suppose you've got two kids playing and one of them says, look at all the stuff on the table; we've got houses and we built cars and we've got airplanes. But the other kid says no, there aren't really any houses and airplanes and cars; it's all just Legos.

Well, whose side would you be on? And is there a real answer to that question? Are there really only Legos there or are there also cars and airplanes and what have you?

What would make you change your mind about that issue?

My suggestion is it's not just a verbal dispute and it has to do with causation. That is, we connect our concept of reality with having causal powers.

So the dispute between the two kids--I think we might tend to agree with the reductionist so long as the things were just sitting there. But suppose the little airplanes started to fly; suppose the little cars started driving around on the table. I think the reductionist would then be inclined to say oh, my gosh, there really are cars and airplanes there.

So my point is that the dispute between the reductionist and the non-reductionist can be recast as a dispute over causation. The reductionist says, in effect, all causation is bottom up; that is, the laws of physics down here determine everything that happens and the causation percolates upward, determining what happens all the way up to the top.

The non-reductionist, on the other hand, says no, there are new causal factors and laws at these higher levels of organization that also have to be taken into account in order to understand what goes on in our universe.

So my question is: How can this be? Remember that for the non-reductive physicalist we're not going to introduce any new non-physical forces or entities, vital forces or psychic energy. So how can the causal properties of these higher-level things really matter? And how can it not be the case that they interfere with or cancel out what happens according to the laws of physics?

This, I think, is the center of the question of reductionism. And the way I want to approach it is by introducing the notion of downward or top-down causation.

This is an idea that was introduced in 1972 by Donald Campbell. But it seems to me that it's been much ignored by both philosophers of science and also by scientists themselves in the years since then. The one place in science where downward or top-down causation does get a lot of attention, I think, is in psychology.

Campbell's claim was that bottom-up accounts in biology are necessary but they're not sufficient, they are only partial. In addition to the bottom-up account in terms of biochemistry, you also need a top-down account to complement it. Here's his example:

He raises the question: How do you explain the fact that the jaws of worker ants or termites are so beautifully designed to do the kind of work that termites do, gnawing wood or the ants carrying seeds. He says from an engineering view they're optimally designed; you could hardly do any better job if you were--with those materials--if you set out to design it yourself. So how to explain that?

Well, the bottom-up account, the termites' genes give instructions for protein formation and the proteins make up the jaw structure. But this explanation is incomplete. How come the lucky termite has that particular DNA instead of some of the countless other possible forms that it could have? How did it come to have the instructions for such useful jaws?

The answer, of course, is natural selection. Though it has been, in the past, random production of lots and lots of variants, and only the useful ones have survived to reproduce. So we have a bottom-up cause in terms of the macromolecules. But we also have to have a top-down cause in terms of the ecosystem in which the little bugs live and the way that that has had a differential effect on the survival and reproduction of the termites as whole organisms.

This diagram, in terms of levels of organization, is static and so it's not the best way to represent what's going on. What we really need is a feedback loop that allows us to take into account changes over time.

And so here I've got the bottom-up part of the explanation, the DNA to protein structure. But then we've also got the top-down part which is from the environment by means of the differential survival and reproduction back to the DNA. And then we start through the whole cycle again.

So downward selection is selectively wiping out a lot of the variation but it's not interfering with the laws of biology and a fortiori it's not interfering with the laws of physics.

So this is a particular example of how top-down and bottom-up causation conspire to produce the world that we've got. We have bottom-up causation that permits a vast number of varieties at all sorts of levels. And then downward selective processes determine which of those possibilities actually exist.

For example, chemistry permits something like 10 to the 200th power of different proteins--a rough estimate. Somebody could probably give me a better number on that but I just want to give you a ballpark figure of what a vast number of possibilities there are for large complex molecules. But not all of those exist.

In order to explain why the certain ones that do exist in the world exist, we have to know how those large complicated molecules fit into biological organisms and biological processes.

So, in sum, life brings new sorts of causal interactions into the world. These are consistent with physics but they're not predictable by physics.

Consider for a silly example the difference between shining a flashlight beam on a pound of hamburger versus shining a flashlight beam on a live animal. The hamburger is not affected appreciably by the light striking it but the animal might jump up and run. The physics of the light beam is the same in both cases but the effect is vastly different.

So the non-reductionist says when you have these more complex structures it's not that there are new causal forces--psychic forces or vital forces or whatever. Instead, the causal forces of physics will enter into vastly more complex interactions. The laws of physics don't predict rabbits but rabbits and their behavior do not violate the laws of physics.

I want to switch now to talking about a non-reductive view not of life but of the mental, and you can probably guess where I'm going here.

There's a perfect analogy between what the non-reductive physicalist wants to say about the mental and what the biologist wants to say about life. Life does not require a new kind of entity, that is, complex bodies have the quality of being alive if they interact with the environment in a special way. Similarly, mind is not a new kind of entity, rather complex living beings have mental qualities if they interact with the environment in a special way.

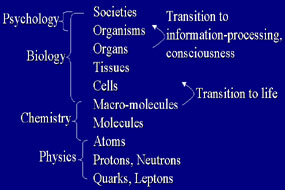

So I've reconfigured the hierarchy a little bit. I've put societies at the top because mental functioning really does require social interaction. So I've added psychology to the hierarchy of the sciences and have indicated roughly a transition to information processing or consciousness.

|

For the present purposes let's see if we can separate out the issues of information processing and consciousness. As has been noted by a number of philosophers, consciousness is really the hard problem but there's a whole lot we can say about information processing, which is equally an important aspect of the mental life.

To show that it's possible to make a distinction between consciousness itself and the information processing aspect of the mental, consider a very interesting case of a neurological defect. These are people who have so-called blind sight; that is, they have damage to their visual cortex so they simply can't see.

But with some of these people you ask them a question--for instance, is there a chair in front of you. And they'll say, well, what are you asking me for, you know I'm blind and I can't see. Well, I know you can't but just guess. Is there one there or not? And when they guess, many more times than they should right out of chance they can tell you that it's there; they can locate objects in what would be their visual field if they could see much better than they could if they were literally blind. And so what that shows is that they are actually taking in information about the world around them and they're processing it at some level so that they can act on it if you force them to but they're not consciously aware of that information. And so that shows that there is a distinction between consciousness and mere information processing.

We could get the same point by trying to imagine the mental lives of very, very simple organisms, worms or whatever. We know that they take in information because if you touch them they move and all that sort of stuff. But we don't imagine that they've got a very interesting mental life and, in fact, I assume that they're not conscious at all.

So even though we don't have any robust theories about the nature--the biological underpinnings of consciousness, the conscious aspect, we do know a whole lot about the neurobiological underpinning of information processing, and you heard a lot about that from our first lecture.

For instance, with vision, we know that we've got two different kinds of receptor cells in the retina. Information from those cells is transmitted by the optic nerve to the brain. And we even know what parts of the brain, as you could see from the beautiful slides, are involved in visual processing. And, in fact, the victims of blind sight, they can find the actual lesions in the striate cortex.

So the mental, as information processing at least, is clearly a biological function. It depends on the organization of certain kinds of cells, the neurons that got great pictures of this morning--capable of transmitting electrical impulses to a central processing organ, for us, the brain. And from that central processing organism to the muscles, etcetera.

Now, consciousness--I won't say very much about this--but recall the title of my talk: Getting Mind Out of Meat. That comes from a line I read in one of Patricia Churchland's books. She says a lot of the arguments against physicalism are of the--I can't see how you could get ever get mind out of meat kind of arguments.

So I just want to take a stand with the objectors who say that understanding consciousness really is the hard part of neurobiology. We do know a lot of things about it, it depends upon a highly complex central processing organ, the brain. It seems to result from the synchronised firing of lots of neurons--and I should say lots and lots and lots of neurons. And we know a lot about how to get rid of it--a bonk on the head, enough alcohol--whatever.

So I would take my stand with other physicalists in that regard and say that there's no good reason to think that we cannot eventually come up with an account of the necessary and sufficient biological conditions for consciousness, just as we can talk about the necessary and sufficient conditions for life.

Now, we may never know details about the phenomenal aspects of consciousness. For instance, why does grass produce the visual sensation that it does rather than the visual sensation that ripe tomatoes produce. Why is green green to us instead of the reverse or whatever.

So this is the physicalist's thesis: The organization and special functions of the nervous system interacting with the body as a whole and also with the environment produce what we call mental functions. Note the adjectival form mental.

So what about the non-reductive part? I said above that the main issue is causation. To say that the mental level of functioning is not reducible is to say that a complete causal account of what goes on in the world has to take it into account.

Now it may be difficult, surprisingly so, to give an argument for the causal difference that consciousness makes. Philosophers fool around with thought experiments -- couldn't we all be zombies and be doing just exactly the same things that we do and would anybody ever know the difference.

But the causal difference made by information processing is totally manifest. For example, the rabbit jumps up when the light is shown on it and the pound of hamburger doesn't. So it's very clear that the rabbit is processing information, and we can just tell that by watching what it does.

In my next lecture, I'm going to talk about downward causation of what we usually think of as the mental ideas, reasons, etcetera. But I'm going to put that off until the next lecture because I want to do that in conjunction with talking about free will.

For now I'm going to turn to a somewhat different issue, that is, the question of the distinctives of the human person. If we put organisms in a hierarchy; viruses, bacteria, sponges, plants, lower animals, mammals, chimpanzees, humans, what are the distinguishing features in the transition from animals to humans?

Now, again, I'm assuming divine creation through evolutionary processes. So I can ask the question in terms of divine action: What did God give us that makes us truly different from the animals?

Many modern religious believers would say that the main difference between us and animals is that we have souls and animals don't. Now I have to specify modern because, as many of you know, for the Medievals it was assumed not only that animals have souls but that plants have souls as well. So the difference between us and the animals is that we have the deluxe version of the soul, not that we have one and they don't.

But again, a non-reductive physicalist says there's no need to postulate the addition of a new kind of entity, a mind or soul. Rather, what we have is more complexity and specific organization for new functions.

We can guess from looking at our brains as compared with chimpanzees that an important factor is that large neocortex that you saw a picture of this morning. And a plausible thesis is that both the larger size of the human neocortex but also significant rewiring of the brain as a whole is what permits us to have sophisticated language; that is, true language as opposed to just calls and signaling that birds and animals have.

Genuine language involves symbolic representation; that is, a sign or symbol can stand not just for a thing but it can stand for an abstract category. It's the difference between knowing to call a certain elderly lady grandma versus having the concept of grandmother. And think of what a sophisticated change goes on in our children when they catch on how to use the term grandmother as opposed to just calling their own grandmother granny or grandma.

Symbolic language then allows for all or perhaps I should say most--but I'm inclined to say all--symbolic language then allows for all of the features that make us distinctively human. I'm going to list for you what I think are seven of the most important features that we have that distinguish us from the animals.

First of all, we have a more refined self-concept; that is, we not only recognize that this is me, my body, when we see ourselves in the mirror, but we have a concept of ourselves as a human being, as a specific member of a family, as an American, as a Christian--whatever. And this distinguishes us from animals with the most primitive version of self-concepts. Certain monkeys, if you put a red spot on their forehead and then put them in front of a mirror, they'll notice that it's there. They'll recognize that it's themselves in the mirror but, of course, they don't have any symbolic representation of myself or me, the chimp, or whatever. So refined self-concept is the first distinctive.

Second, given that refined self-concept we have the ability to represent to ourselves the concept of other people's minds. That is, I realize that I'm conscious, that I have ideas but I also realize that you are conscious. And so I can think about what you think. I can think about what you know; I can think about what you are ignorant of. Chimpanzees can do this to a small extent, they can be aware of the fact that a chimpanzee in another position can't see what it sees. So it's a difference of degree. But we can have very sophisticated representations of what other conspecifics have in mind.

Third, we have the capacity for true morality. Now, as you probably know, there's a lot of debate among sociobiologists as to whether altruism is genetically determined. But I want to distinguish between so-called animal altruism because it's genetically determined and human altruism--human morality--which is based on having the concept of right and wrong. So again, language plays a crucial role.

Fourth, language gives us the capacity to form complex social structures. Now, animals have social structures of a sort but they can't be as complex as ours. We, for example, can write bylaws and laws and constitutions. And so there's the quantum leap in the complexity of the social structures that we can devise.

Fifth, we have the capacity to anticipate death. Again, I think this depends on concepts: I'm human; all humans die, therefore, I'm going to die.

Sixth, we have the ability to ask questions about what is ultimately important; that is, we can ask about the ultimate cause of everything; we can ask about whether the whole has a purpose. And, in short, we are able to ask what's traditionally been understood as religious questions.

And, finally, language gives us the capacity to conceive of God or Gods. It may be that prehumans had stirrings of religious awe or wonder but they could not have a concept of God without having concepts. And so language is an essential mediator of our ability to have religious beliefs.

So here's the physicalist's side. The main thing that accounts for human distinctives; morality, cultural, and religion is language. And the main thing that accounts for language is our large neocortex, plus the rewiring of the brain that goes along with that. And here I'm following Terrence Deacon in his book, The Symbolic Species, which I found fascinating and would recommend to you as a good read.

So the physicalist's part is it depends on the brain. But here's the non-reductive part in a nutshell: Those mental constructions that involve language make a real causal difference in the world. We can see that this is true. Laws make human beings behave differently than they would have otherwise. Belief in God results in different behavior. And it even results in there being different physical objects in the world than there would have been in the world without it. For example, you can think of churches as monuments to--if nothing else--the causal efficacy of belief in God.

In my next lecture, what I'm going to try to do is put all of these pieces together with a concept of the downward causation of the mental in order to reconcile the notion of mental causation and free will with neurobiological causation. But I stop here and I have saved you 20 minutes to ask me questions.